CAPE MAY POINT – The first spoken sentence in “Moon Crabs,” Leah Michaels’ short film about horseshoe crabs, is a muttered expression of confusion: “I do not understand.” The muttering comes from Dr. Abner Lall, a respected neuroscientist whose breakthrough research on horseshoe crabs ushered in a new understanding of the connection between the brain and the eye.

But here he is, fumbling with old slides. The projector won’t play along. The opening scene is dark. In front of the camera is a living room in a cozy mid-century styled home. There’s more fumbling. Leah, finally, gets the projector to work, and the presentation, from one of the world’s leading experts on horseshoe crabs, begins. It’s one of a few huzzah moments of clarity sprinkled throughout the 11-minute short film.

Much of the film is shot at local spots like Reed’s Beach and Cape May Point. Leah grew up here; her family has come down the shore since the 1970s. She remembers being fascinated by the animals when she was a kid, even as their gnarly prehistoric look frightened other children.

Moon Crabs presents a lot of information quickly but trusts the audience to digest it all. It’s full of fresh visuals, of things that shore-locals are familiar with but perhaps haven’t studied closely in a while. A standout scene shows horseshoe crab eggs under a microscope, where minuscule horseshoe crabs wiggle and squirm like alien creatures.

Another moment of clarity comes later in the film. The camera dives underwater, and the sound gets loud and claustrophobic. The audience sinks briefly into the bottom-feeding world of the horseshoe crab.

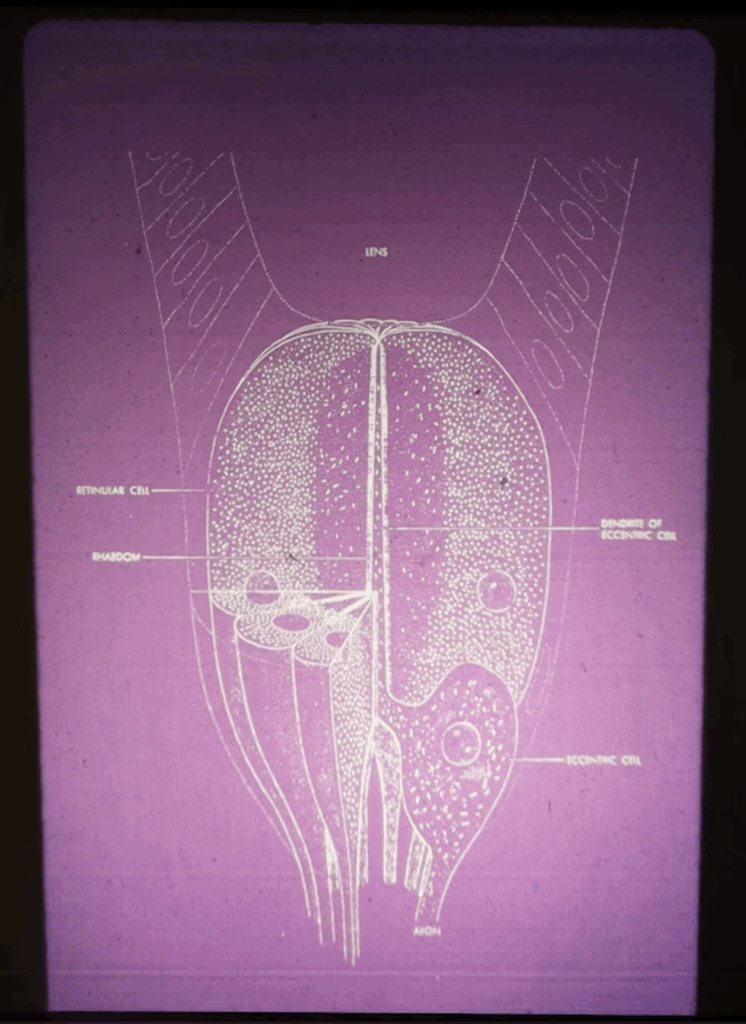

But then the water recedes, and all that is left is the bright light of the full moon. The moon, Dr. Abner’s research showed, plays a huge role in the life cycle of a horseshoe crab. The film is called “Moon Crabs” because horseshoe crabs can see UV light that shines off the moon, guiding them to the Delaware Bay in massive groups to mate. They have done this for millions of years, their physiology and behavior patterns changing negligibly even as other animals changed forms entirely.

Dr. Abner, in a soothing, raspy voice, tells the audience that the horseshoe crab’s simple structure makes them easy to study. Before his work, researchers did not truly understand how information was transferred from the nervous system to the brain. Studying horseshoe crabs made the connection obvious.

Experimental techniques are used throughout the film, but they never feel disruptive. Some shots are hazy, like squinting at a faraway horizon. A snowy egret flies by the wetlands in one of these blurry scenes. If you pause the film, it’s hard to know what you’re looking at. But the motion and colors give enough information for the viewer to make it out. It’s fitting, because horseshoe crabs themselves have shabby eyesight but process just enough to get where they need to be.

Much of the film was shot on analogue equipment and developed using made-at-home chemicals. “You can take seaweed, certain plants and flowers, and kind of make a ‘tea’ and mix it with vitamin C powder and soda washing powder,” Leah told Do the Shore about her development process.

A lot of filmmaking is wasteful and relies on environmentally taxing processes and equipment, she said. This is especially true in the age of artificially generated images and text, which consume gratuitous amounts of resources to produce a final product.

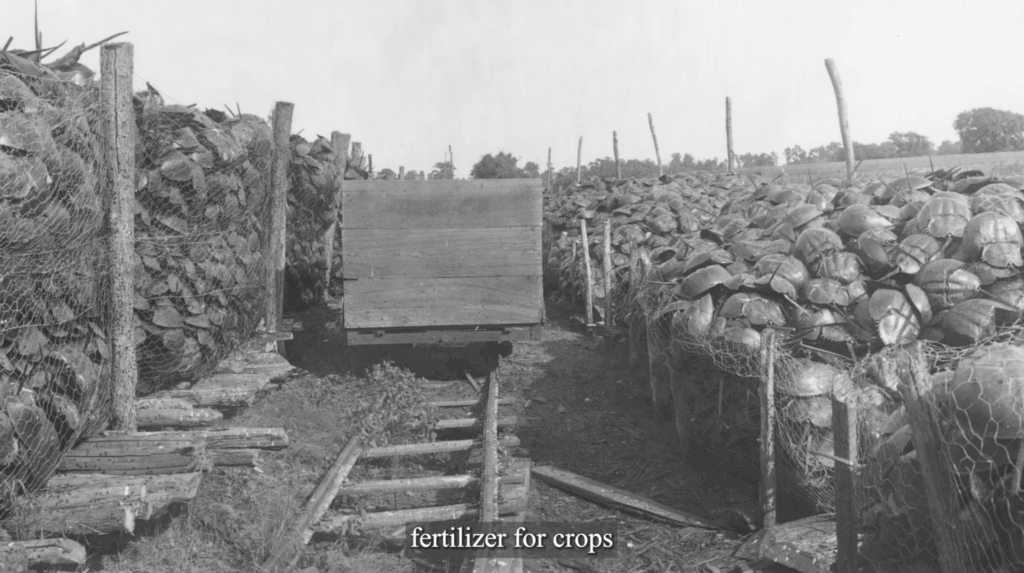

At the heart of her film is a message of conservation. Leah contrasts harsh images of mass horseshoe grab graves with shots of them swimming and mating undisturbed.

Death and consumption have always been part of the natural world. Shorebirds, like the Red Knot, eat horseshoe crab eggs to survive. But the natural world has a way of self-regulating without throwing the larger ecosystem into turmoil. “Moon Crabs” cautions against over-indulging.

The film ends with a quote from Dr. Abner, who speaks from a long lifetime of studying nature.

“You can not build a nature. You have to learn how to work with how nature is working,” he said.

There will be local screenings of the film later this summer at Ostara’s Coffee House and, if all goes to plan, the Cape May Library. It has been screened at many international film festivals.

Contact the author, Collin Hall, at chall@cmcherald.com – Collin is the editor of Do the Shore.