NORTH WILDWOOD ─ “Dear Mr. Bedard: I am very pleased to inform you that you have been awarded the insignia of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the President of the French Republic, Mr. François Hollande.”

So penned Bertrand Lortholary of the French Consulate in New York, informing Henri Bedard of his award from France. The Aug. 24 letter reached Bedard’s “humble abode” and was followed by a second letter from the French Consulate Oct. 12.

In the second letter, Bedard was told that his award “Underlines the deep appreciation and gratitude of the French people for your contribution to the liberation of our country during WWII. We will never forget the commitment of American heroes like you to whom France owes so much.”

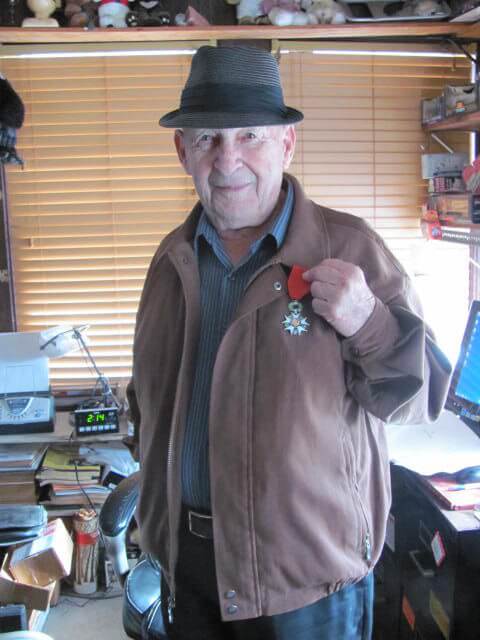

Bedard, 92, showed copies of both letters, citation, and medal. After attending the ceremony in New York City Nov. 6, Bedard, in the comfort of his home, summed up his war experience: “I did what I had to do.”

Berdard’s story began in October 1923 on a dairy farm in Champlain, N.Y., near the Canadian border. Bedard’s path in life led him to Washington, D.C. where he worked for the federal government.

Bedard was drafted and served in the 83rd Infantry Division, known as the “The Buckeye Division,” in 1944.

“I did what I had to do,” Bedard said simply, listing battlefields on which he fought: Omaha Beach, the Ardennes, Battle of the Bulge, and on the banks of the Elbe River – places often never seen except in war films or documentaries.

Bedard described the Army engineers who constructed bridges in order to cross the river. “There was a whole bunch of people,” said Bedard.

He continued his tale, moving forward to war’s end. Bedard returned to the states and took up his job as an insurance underwriter. “I didn’t like it,” Bedard said.

After settling for a time in Philadelphia, Pa., Bedard managed a gas station and repair station until he heard of North Wildwood, and bought what is today Henri J’s.

Bedard laid roots into the sandy soil of North Wildwood in 1951, serving many residents and tourists for generations. Time passed and his children grew up in the community – today, Hank Bedard carries on the family business.

When asked if he ever returned to France, Bedard replied with a smile, “Oh, yes, many times.” Bedard even went back as interpreter and claims that, no matter the dialect or accent, “French is French.” “I didn’t speak English until I was 15!” Bedard added with a grin.

Dorothy Kulisek, editor and publisher of The Sun, has known this quiet hero since childhood. “My grandparents were his customers,” Kulisek explained. “I knew her before she was born!” Bedard said, laughing.

Bedard, one of thousands who helped in the liberation of Europe from the clutches of Nazi rule, is a living link to the past, to the brave men and women who served at home and abroad when the world was engulfed in the horrors of war.

Fluent in French, Bedard has navigated the waters between two cultures. “Everything is a gamble,” Bedard stated. From games of chance and skill to the forests of Luxemburg, Bedard said he looks for “the anxiety of the unknown.”

The cross-shaped medal newly awarded him still bears its luster, testifying to Bedard’s title of Chevalier, the French equivalent of knighthood. “Chevalier of the Legion of Honor” guilds the citation, signed by President François Hollande and other dignitaries. This quiet, unassuming knight has seen great changes, struggles, and advances in the world, reminding us that Henri J’s garage is more than your ordinary repair station.

To contact Rachel Rogish, email rrogish@cmcherald.com.