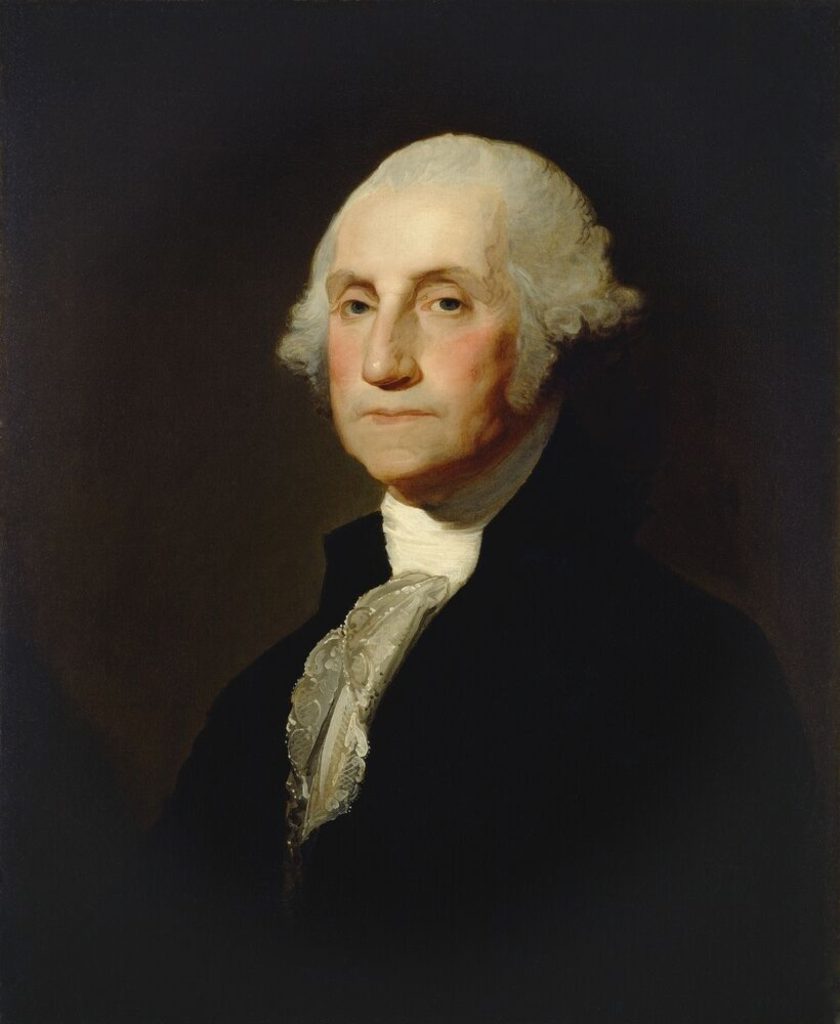

We annually celebrate the birth of George Washington as one of the most preeminent of our founding fathers. He was the military man who saw us through a war with the world’s greatest military power. He served as the trusted symbol who was unanimously elected president of the Constitutional Convention. He agreed to come out of retirement to become the reluctant first president, playing midwife to the new constitution’s form of government.

None other than King George III, who had lost his North American colonies in the Revolution, called Washington “the greatest character of his age.”

Through it all, Washington never let the pursuit of power govern his actions. After the signing of the peace treaty in September 1783 and the final withdrawal of British troops from New York Harbor in November of that year, Washington could easily have pushed aside a flimsy congress and held power in the new nation, a Napoleon before Napoleon. Instead, he elected to resign his commission.

On Dec. 23, before the Congress of the Confederation meeting in Annapolis, Washington surrendered his commission in a ceremony captured in John Trumbull’s famous painting. Calling it the “last solemn act of my official life,” Washington commended the nation’s future “to the protection of Almighty God” and retired to Mt. Vernon. He was 53 years old.

When the artist, Benjamin West, informed George III of Washington’s intentions to resign, the king said, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.” For Washington, this was but the first time he would surrender power that was his for the taking. “I retire from the great theater of action,” a seeming Cincinnatus returning to his plow. Pulitzer Prize winning historian Gordon Wood called Washington’s relinquishing of power in 1783 the act that was “the greatest of his life.”

He would again step away from power in 1787. It was Washington who set the tradition of a president serving no more than two terms. That tradition was not enacted into law until the mid-20thcentury. Washington withdrew from the presidency at a time when he had grave doubts about the ability of the American republic to survive.

Informed as we are by hindsight, we often lose sight of the precarious position of the early republic. The British had not yet given up their designs on American territory. When Washington left the presidency, the British still garrisoned forts along the western frontier. But for Washington, it was important to withdraw from power and show a path forward for this radically new form of government.

The Articles of Confederation had been pushed aside, a new constitution had been ratified, a Bill of Rights had been defined. Washington’s selfless action gave the new constitution, one for which he had grave concerns, the opportunity to succeed without him.

It is now the oldest continuously operating instrument of government in the world. The Bill of Rights provided its first 10 amendments in 1791. Only 17 more would follow in over 240 years.

Washington’s death in December 1799 came just short of the dawn of the 19th century. There was an outpouring of grief in the nation. It was then that Light Horse Harry Lee, the father of Robert E. Lee and a longtime friend of Washington’s, uttered in a eulogy one of the most succinct and lasting characterizations of the great man, “First in War, First in Peace and First in the Hearts of His Countrymen.”

Almost immediately, the nation entered into an acrimonious election defined by mudslinging, attacks and counterattacks. The election of 1800 is often credited, for good or ill, with giving us the two-party system we still live with today.

The Democratic Republicans bested the Federalists in that election, with 53% of the vote versus 47%. Thomas Jefferson unseated John Adams as president. The nation next entered a period of intense internal conflict that saw a second war with Britain and culminated in a Civil War. Through it all, the nation persevered and healed. Power was transferred peacefully. Strongly held beliefs gave way when necessary and compromised where they could.

Political faction was one of the things that most worried Washington. For him, this was a great experiment in which a nation had to prove that a government based on the consent of the governed and not the power of kings could endure. Washington knew that a large-scale republic would be open to tumult and conflict, but he was willing to see if the inherent virtue of the governed would pull it through.

Trumbull’s painting of Washington’s surrender of his commission in 1783, the act so many saw as his greatest, can aptly be viewed in the U.S. Capitol rotunda.

———-

From the Bible: The second most important command is this: ‘Love your neighbor the same as you love yourself. These two commands are the most important.” Mark 12:31