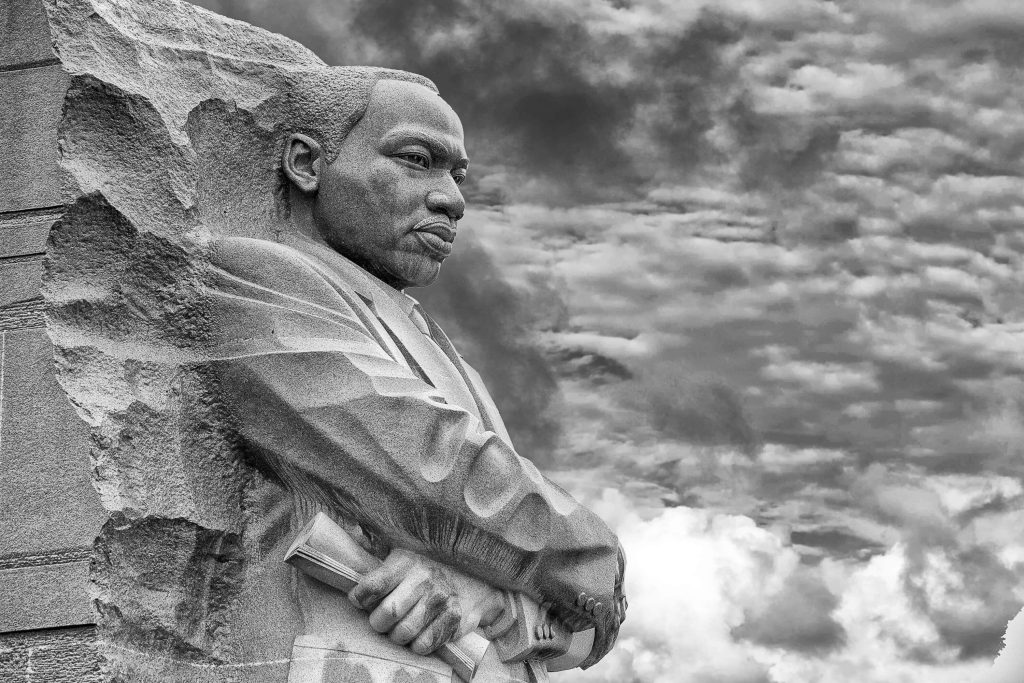

On Jan. 17, the nation will again celebrate the birthday of Martin Luther King. King was born Jan. 15, 1929.

The man we celebrate on this national holiday is the king of the Birmingham campaign in 1963, the king of the March on Washington, the king who is a symbol of the struggle for racial justice using the techniques of nonviolence. King’s method used nonviolence to put the evils of racism in view before the American public. This is the king of the “I Have a Dream” speech. In many ways, he has become more symbol than man.

—————–

It is hard for us today to appreciate the enormity of the impediments that King faced as he tried to extend America’s founding principles to all Americans.

—————–

In 39 short years of life, King had an enormous impact on American society. The society King sought to reform condoned laws like the one in Birmingham, Alabama, that made it a crime for “a Negro and a white person to play together.” That ban extended to a game of checkers or dominos. Segregation was complete and legally enforceable. Voting rights were routinely ignored. Violence against Blacks, and even lynching, were all too common events.

King’s arrest in 1960 led to the famous call to his wife, Coretta, from Sen. John Kennedy. It was a call that might have swung enough votes for Kennedy to edge out Richard Nixon who campaign advisors urged silence on the issue of King’s incarceration. Such was already the influence of King at barely 30 years old and before his most eventful years.

King left America better than he found it. The reform he sought had much yet to be accomplished when he was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968. Yet, King’s influence was substantial. His optimism that the goals of racial equality could be achieved were tarnished in his final years. King was not blind to the enormity of the challenge his campaigns for racial equality placed before an America that had engaged in, condoned, or ignored persistent racial injustice.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 followed the March on Washington. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 came on the heels of “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama, in March of that same year. King’s nonviolence campaign for civil rights appealed to America’s sense of its founding principles by putting on display some of its worst demons.

As a man, King was flawed, as are we all. His appetite for sexual indiscretions fueled attempts by the Federal Bureau of Investigation to undermine and even destroy him. He was not a blind optimist when confronting racism in our society; rather he was a solid realist who knew the enormity of the task in front of him.

In a speech at Stanford University in 1967, King spoke of those segments of American society that cared more “about tranquility and the status quo than justice, equality and humanity.” Earlier in his famous 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King noted that major obstacles to his efforts were those moderates who “were more devoted to order than to justice.”

It is hard for us today to appreciate the enormity of the impediments that King faced as he tried to extend America’s founding principles to all Americans. One thing he knew is that he might not live to see the results of his efforts.

In his famous last speech just 24 hours before his assassination, King spoke of going to the mountaintop to see the Promised Land of racial equality. He knew the journey would be long and dangerous. He admitted, “I might not get there with you.” His assassination the next day proved him prescient.

On this holiday, we should choose to remember a complicated man who, in a short life, accomplished much that made our society better.

——-

When justice is done, it brings joy to the righteous but terror to evildoers. Proverbs 21:15