CAPE MAY – The underground railroad, a social justice movement that helped enslaved people on the run, was neither underground nor a railroad, but used railroad terms as code words during its reign in the early and mid-1800s.

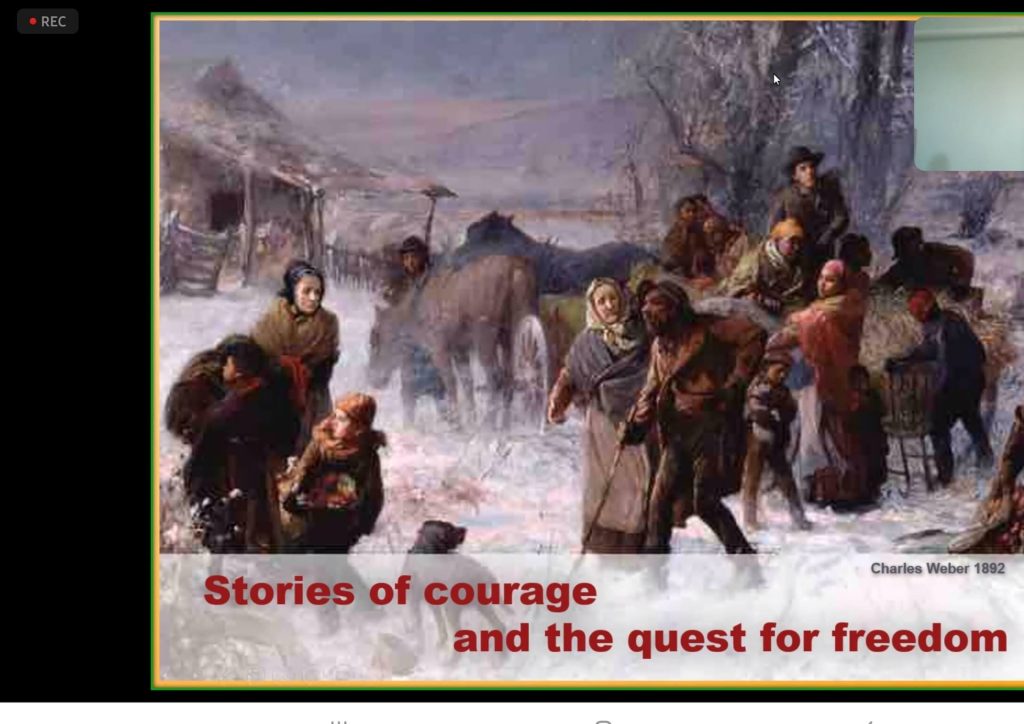

According to Ted Bryan, a retired Middle Township High School teacher and nearly life-long resident of the area, the underground railroad is considered the first Civil Rights movement as it impacted people who were old and young, Black and white, traveling in tough weather conditions, mostly in spring and winter.

He shared the history of the underground network in Cape May and tales of some of its supporters during a lunch and learn Oct. 19, sponsored by the Cape May Museums+Arts+Culture (MAC).

“Safe houses were called stations,” Bryan said. “Guides were considered conductors; station house owners were station masters. Many of the routes were up through the central U.S., down to Mexico or north to Canada.”

The route to freedom for enslaved persons began in the early 1800s and reached its peak from 1850 through 1865, according to Bryan. Nearly 100,000 people escaped to freedom, often traveling 10 miles during the night.

Bryan gave an overview of a number of federal laws that sided with slave owners, including the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which punished anyone who didn’t help in the capture of the slaves and prohibited enslaved people from fighting kidnapping charges in court.

The Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves in 1863, and the 13th Amendment banned slavery in 1865.

“The lighthouse of Cape May became the beacon of freedom for many,” Bryan noted. “South Jersey and Cape May were actually very divided on the issue because it was a vacation spot for visitors from the North and South. New Jersey banned slavery in 1846, 14 years before the start of the Civil War.

William Still is considered the “father” of the underground railroad, leading efforts in New York, New Jersey, Delaware and Pennsylvania. He often would talk with the freedom seekers, according to Bryan, capturing their stories and eventually publishing “The Underground Railroad Records” in 1872.

One story Bryan told was of six Black men who bought a boat to escape from Maryland. They ended up in Cape May on the beach near the lighthouse. A local oyster boat captain took them to Philadelphia for $25.

Another story concerned a sea battle in 1831, where two masted sailboats appeared off the shores of Cape May with about a dozen Black slaves from Virginia. It appeared the boats were being chased, and some of the local Cape May boaters joined in the chase. Thomas Hand was killed in the chase and the freedom seekers ended up sailing to New York.

“Harriet Tubman worked in some of the hotels in Cape May during the summers in the 1850s,” he said, using her wages to finance rescue missions. Cape May was a branch of the main underground railroad heading north, and there were two Black communities within the county at the time: one in Lower Township below the canal, and the other near what is now the Cape May National Golf Course. Tubman is said to have rescued at least 70 slaves on 19 trips to freedom.

A museum honoring her efforts and providing historical information about the underground railroad in Cape May is open on Lafayette Street, Cape May.

Bryan noted a number of abolitionists and enslaved people who passed through Cape May, including Joseph Leach in the 1850s. Leach was editor of the Cape May Ocean Wave and his historical house is on Lafayette Street, Cape May. Bryan also highlighted the Owen Coachman house and Batteast House off Shunpike Road in Lower Township.

There was also Steven Smith, who was born enslaved and then became one of the richest lumber and coal barons in Columbia, PA, whose summer home is on Lafayette Street, Cape May.

In addition, there are a number of Black cemeteries in the area, including Mt. Zion Cemetery on Shunpike Road, West Cape May, where the great, great, grandniece of Harriett Tubman, Florence Cooper, is said to be buried. There is also the Union Bethel Cemetery, on Tabernacle Road, Erma. Civil War soldiers are also buried there.

“The underground railroad is remembered today as an example of bravery, of people working together at great risks to themselves, doing what was right,” Bryan said. “That’s what we champion today.”

Thoughts? Email kknight@cmcherald.com.

Cape May County – Did i miss something? I am watching the defense secretary hearings and I keep hearing Republicans and nominee Hesgeth commenting on how tough Trump will make our military. So, are they saying it isn…