One of the most fundamental obligations of society is to provide its youth with the knowledge and skills to lead productive lives as adults. Thus it is essential to provide all youth with a solid foundation in literacy, numeric, and thinking skills for self growth, employment and life long learning. But as we move into the second decade of the 21st century there is continuing evidence that we are failing a substantial portion of them. One consequence of not providing our youth with the skills to be successful in today’s and tomorrow’s economy is that our country is rapidly losing its competitive edge.

Traditionally we have used the benchmarks of high school diplomas, entry into and completion of college as the measure of success in educating our youth… Under the mandates of No Child Left Behind states have developed testing processes aimed at showing our schools’ success in preparing youth for ‘life.’ We have also developed a strong belief that in order to be successful our children must go to college.

Since the publication of “A Nation At Risk” in 1983 there has been a steady flow of reports and studies that show our system for preparing young people to lead productive and prosperous lives is seriously flawed. Failure to correct our deficiencies is eroding the basic fabric of our society. The American dream rests on the promise of economic opportunity and a comfortable life for those willing to work for it. Failure to provide our youth with marketable skills is leading to an expanding group who are frustrated with scarce and inferior opportunities. The quality of their lives is declining while the costs they impose on society are growing, and many of their potential contributions to society are lost.

The passage of the Higher Education Act in 1965 opened the doors for all students to enter college. The act provided grants and loans for tuition and established the TRIO programs to provide assistance to disadvantaged students. Most states enacted legislation to create the community college systems as ‘open doors’ to the higher education system. However, what was not done was the clear establishment of criteria for the exit standards from high school to be the entrance standards for college. This lack of alignment has resulted in many high school graduates not being prepared for college-level courses.

It is important to understand that ‘being in college’ and actually ‘being enrolled in college-level course’ are two very separate things. National data indicates that some 30 percent of ‘college’ students are not taking college-level courses. Instead they are enrolled in remedial or developmental courses. Gov. Christie is quoted as saying nearly 20 percent of the students at Rutgers are enrolled in developmental courses. At some of New Jersey’s community colleges the number is greater than seventy percent.

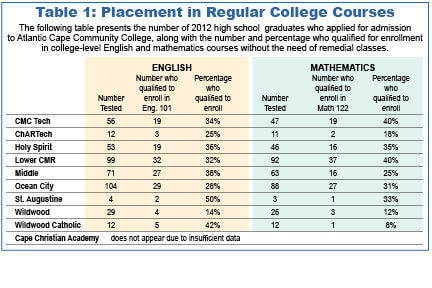

Table 1 shows the number and percentage of Cape May County students, who graduated in 2012, that have been recommended for college-level English and math. Not listed, but easy to calculate, is the percentage that has been recommended for the remedial and developmental courses. The data indicates that local high schools are not adequately preparing students to enter the local community college. How local high school graduates do at other colleges is not known due the lack of reported data.

Each year an estimated 1.7 million American students are directed into remedial/developmental courses According to Complete College America, a Washington-based non-profit, the expense for these courses now costs about $3 billion. Placing students in three levels of remedial math is really taking their money and time with no hope of success, states Stan Jones, president of Complete College America. Research by Thomas Bailey, at Columbia University, looked at students in need of developmental education and whether these students are successful in postsecondary education. His paper concludes that most developmental education is ineffective in helping students overcome academic weaknesses. These findings are staggering when one considers the cost, that in addition to the $3 billion for offering the developmental programs, of the hundreds of millions of dollars the federal and state governments spend to provide additional support to disadvantaged students through programs like the federal TRIO programs and state programs like New Jersey’s Educational Opportunity Fund (EOF).

Directly related to the issue of college developmental education is the number of students who don’t complete the remedial coursework. It is estimated that 15 percent of all students entering a New Jersey community college drop out after their first year. Based on 2008-2009 data these dropouts cost state and local governments about $13 million (The Press of AC, Oct. 22, 2011)

The numbers enrolled in developmental courses have resulted in a fundamental change in how college information is reported. In 1989, the U.S. Dept of Education published regulations requiring colleges to report completion rates based on 150 percent of the time required to complete a degree. Under these regulations, two-year colleges now report completion data based on three years from when the student entered, similarly, four-year colleges report data based on six years. The extra time means that more students take additional time to complete their degree. This additional time means that colleges receive more money in terms of tuition and fees. Some have argued that the additional time is being manipulated by restricting course offerings to increase revenue.

Table 2 shows the completion rates for area two and four-year colleges.

The cost of student loans is directly related to the increased time issue. The media is continuing to report on the mounting student loan debt. In 2011 the total outstanding student debt crossed the $1 trillion mark – an amount that is greater than the nation’s credit-card debt. The default rate on student loans was 13.4 percent with private student loans accounting for more than $150 billion of the total. Economists are viewing the growing student loan crisis as parallel to the mortgage-lending crisis. Students are qualifying for large loans with no regard to their ability to pay back the money. To compound the problem, parents are co-signing for the loans. When the student drops out or graduates and can’t find a job (it is estimated that 54 percent of recent college graduates are unemployed or underemployed) the parents are on the hook to repay the loan ( The Chronicle of Higher Education, Oct. 2012). Many articles about the student loan crisis include human interest segments about individuals who are college graduates, can’t find employment and consequently can’t repay their college loans. It is difficult to assess these individual situations unless one examines circumstances such as: the type of institution(s) attended the selected program major, and the individual’s academic competency.

A COLLEGE DEGREE: NOW WHAT?

It has been drummed into students and their parents that to make it in life one must go to college and work hard to obtain a degree. To do this, students and their parents drain savings and take out huge loans to pay for it all. For the 56 percent of college students who do graduate, after six years, the question is “how can the degree help me?” Several studies provide a disturbing answer—not much.

In the book, “Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses,” Arum and Roksa report on their study of more than 2,300 undergraduates. Forty-five percent of the students showed no significant improvement in the key measures of critical thinking, complex reasoning, and writing by the end of their second year.

Half of the students did not take a single course requiring 20 pages of writing and one-third did not take a single course that required as least 40 pages of reading.

Similarly, a 2011 study by the Pew Research Center found that nearly half of the respondents felt that “higher education fails to provide students ‘good value’ for the money they and their families spent.” In the poll respondents also said that college was unaffordable for most Americans and almost half said that student loans made it harder to pay other bills.

In addition to the students’ perception of their education, a 2012 Employer Hiring Survey, conducted by the National Federation of Independent Business, adds the employer perspective. There were 147,000 employers who reported on their efforts to hire one or more employees. Seventy-six percent found few or no qualified applicants at a time of high national unemployment.

The listed reasons for not hiring were: lack of required skills (26 percent); poor work history (23 percent); poor attitude (17 percent); poor social/ people skills (16 percent); poor appearance (14 percent); and deficient English / math skills (11 percent).

In general terms, a college degree provides some advantage in finding employment and starting a career. However it is important to understand the link between the selected college major and one’s employment potential.

Kiplinger examined and ranked college majors using five criteria: unemployment rate by major, unemployment rate of recent graduates; median salary by major; median salary of recent graduates; and projected job growth for the field for the next 10 years. Based on their analysis the top ten college majors for obtaining a lucrative career are:

1. Pharmacy and

Pharmacology

2. Nursing

3. Transportation

Sciences and

Technology

4. Treatment Therapy

professions

5. Chemical Engineering

6. Electrical Engineering

7. Medical Technologies

8. Construction

Technologies

9. Management Information Systems

10. Medical Assisting Services

Conversely, Kiplinger, using the same methodology, identified the 10 worst college majors for one’s career. Salary.com used the total cost of the degree and the median cash compensation over 30 years to compute a “return on investment” to identify the eight college degrees with the worst return on investment. The two lists are:

Kiplinger

1. Anthropology

2. Fine Arts

3. Film and Photography

4. Philosophy and Religious Studies

5. Graphic Design

6. Studio Arts

7. Liberal Arts

8. Drama and Theater Arts

9. Sociology

10. English

Salary.com

1. Communications

2. Psychology

3. Nutrition

4. Hospitality / Tourism

5. Religion / Theology

6. Education

7. Fine Arts

8. Sociology

While there are no set criteria to guide one’s decision to go to college and what college to attend, various studies suggest the usual factors include: the desire to get away from home, the attractiveness of the campus, the school’s athletic programs, and location in terms of one’s personal interests, e.g. warm weather, outdoor activities. Claudia Dreifus and Andrew Hacker, co-authors of ”Higher Education? How Colleges Are Wasting Our Money and Failing Our Kids” suggest the following questions when considering a college:

• Will college professors be there and teaching undergraduate courses?

• Does the college make undergraduate teaching a priority?

• Is the college overrun by administrators? What is the ratio of full-time faculty to people in non-academic jobs?

• How much emphasis is on athletics?

• Does the financial aid office level with you? Today, what’s called aid is usually a discount on the sticker price.

• Does the campus resemble a resort. These fad items are added on to students’ fees, diverts funds from teaching, and explain why so many courses are taught by low-cost adjuncts or graduate assistants.

The price at the type of institution selected will vary according to whether it is a two-year college, or a public, private or for-profit four-year institution. If one selects to start out at a two-year college and then transfer to a four-year college for the last two years it is very important to get the details of the articulation agreements between the two institutions. In many cases, the transferring student is not granted full recognition for the courses taken at the two-year college and forced to take extra course work beyond the normal 128 credit hours for a baccalaureate degree.

Other questions that should be asked of prospective institutions include:

• What is the graduation rate after four years? After 6 years?

• How many graduates are employed in their field within six months of graduating?

• How long does it take a newly-hired graduate to get their first promotion?

• Is the degree-specific curriculum established by the faculty or an industry advisory committee?

OTHER OPTIONS:

Despite decades of efforts to reform our education system, and billions of dollars of expenditures, the harsh reality is that America is still failing to provide millions of its youth with the knowledge and skills to be productive members of the workforce and to have successful lives as adults. Evidence of this failure is everywhere; in the dropout epidemic that plagues high schools and colleges; in the harsh fact that just 30 percent of our youth earn a bachelor’s degree by the age of 27; and in the teen and youth adult unemployment rate. It is the belief of the leaders of the Pathways to Prosperity Project at Harvard University that “ unless we are willing to provide more flexibility and choice in the last two years of high school and more opportunities for students to pursue programs that link work and learning, we will continue to lose far too many young people along to graduation.”

The Pathways to Prosperity project contends that our national strategy for education and youth development has been too narrowly on an academic, classroom-based approach. The recommended changes are based on two elements:

1. Schools need to broaden the education experience by embracing multiple pathways to help young people successfully navigate the journey from adolescence to adulthood.

2. Employers need to play a greatly expanded role in supporting the Pathways system by providing more opportunities for youth to participate in work-based learning and in jobs related to their programs of study.

Over the past 20 years there have been many initiatives to reform secondary education and facilitate a smooth transition to postsecondary education. Among the more successful approaches have been the High Schools That Work program developed by the Southern Regional Education Board, the Career Academy/ Magnet School approaches, and the Two Plus Two Tech Prep Associate Degree Program.

All of these approaches have demonstrated success and stress a rigorous academic curriculum, work-based learning opportunities, greatly expanded time both in terms of a daily schedule and a longer school year.

Examples of these approaches in New Jersey would be the academies operated by the Bergen and Monmouth county vocational school districts and which are routinely ranked as among the best high school programs in the country. Perhaps the best model for a school/business partnership would be the National Academy Foundation, that has refined a proven education model which includes industry-focused curricula, work-based learning experiences, and business partner expertise.

Not to be overlooked in the discussion of education reform are apprenticeship programs which for thousands of years were the way youth were prepared for careers. Apprentice training combines work-based learning, under the direction of a master craftsperson, with theoretical learning known as ‘related training.’ Often looked down upon by the academic elite, apprenticeship is a proven educational model that has a far greater success rate than our present high school/ college systems.

The economics of apprenticeships are far better than pursuing a college degree. Each year during the four- or five-year apprenticeship the individual is earning an increasing rate of pay. At the conclusion of the apprenticeship, the journeyperson is earning a salary greater than the average college student and does not have any college loan debt.

A recent study in Wisconsin found that the difference in cost to the state between apprentice training costs and university student education costs is $ 10,043 per year. Recently CBS News highlighted the value of Boston’s sheet metal worker’s apprenticeship program. Graduates of the five-year program average $ 40 to 50,000 per year, are 23 years old, and have no college debt.

In the mid 1970’s, the American Council on Education developed a partnership with the George Meany Center for Labor Studies to evaluate AFL-CIO apprenticeship programs for the purpose of recommending college credit for their apprenticeship experience. Many of the programs have been recommended for some 30 to 40 credit hours. Thus the apprentice can be working toward a college degree while earning their journeyperson certificate.

CONCLUSION

The data on high school and college drop-outs, college developmental studies, and college completion rates lead one to the conclusion that our education system is broken. As a consequence, our country has lost its competitiveness at a time when higher levels of technology are driving the economy of the 21st century.

The titles of two of the most important education reform reports of the 1980’s and 1990’s are even more relevant today : ”America’s Choice: High Skills or Low Wages and The Forgotten Half – obstacles faced by non-college bound youth in today’s economy.”

At a time when the taxpayer is being given ever increasing bills for the education system, the public must demand that our political and education system produce better results. Accepting the status quo is leading our country into a disaster.

ABOUT DR. HENRY

Tom Henry began his academic career in 1967 teaching Biology at Cumberland County College. Over the next 23 years he served in various administrative positions including Dean of Career and Technical Education and Vice President of Development. In 1991 he was named the Assistant Commissioner of Education in the N.J. Department of Education. His Office was responsible for Vocational Education, Adult Education, and the State Apprenticeship program.

Nationally, he was named an Academic Fellow to the American Council on Education in 1978. He also served on the National Boards of the National Council for Resource Development and the State Directors of Vocational and Technical Education as the Chairman of their Legislative Taskforces. In 1999 he was appointed to the Federal Government’s Workforce Excellence Board.