As we celebrate holiday family traditions, many of us look back in time to childhood days when our parents seemed wiser than we could ever be. At these times I salute my dad, whose vision and courage supported his six siblings after his father died young, leaving him “head man” at 15.

His mother spoke no English. His capacity to endure hardship and achieve success became my model of survival when I faced sudden widowhood at a young age. I hungered to understand his beginnings but had not taken time to ask him during our nearly 50 years together. He was just “Dad,” funny, wise, patient, and usually correct.

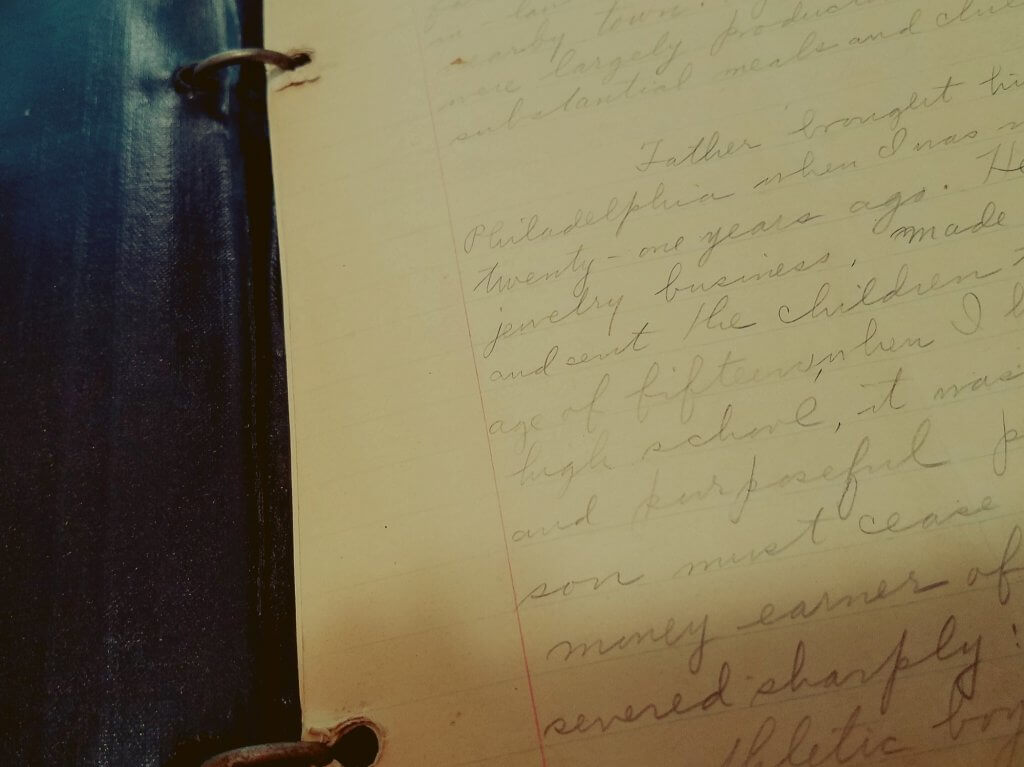

This week, seeking stories from my ancestors, I remembered unearthing an 8-by-11 inch folder with yellowed line papers bound by two metal rings that snapped together.

I had never read it closely. I easily found it again on the shelf in back of my desk. The feel of the black shiny cover was bumpy as I stroked the texture with the palm of my hand to intensify the feeling of being with my dad.

I opened it to find penciled handwriting that I recognized as my father’s. Some 75 years on one shelf or another had smudged the penciled script but, taking it into the bright light over my desk, I was thrilled to see that, if I worked at it, I could discern the text.

My father, the patriarch of a successful clan numbering 45 cousins most of the time, had a quick wit and sly humor that snuck up on you and created a ripple in your lower lip as you realized the depth of the one liner you had just heard him casually drop into a conversation.

His humor ranged from a slow burn to a sudden jab of truth between the ribs. Since I never heard his story as fully as he could have told it, this brief autobiography in his own hand brought memories flooding my awareness, throwing me back to the days where Dad was “the man” in my life.

These intact pages were titled “Lesson 1. Autobiography, Louis Milner, Oct. 18, 1927.” Here was the truth. Eyes wide with astonishment, heart racing with the chase of discovery, I read,

“I was born in Belo-Tzerkov, near Kiev, Russia. My father was a jeweler and owned the jewelry shop of the town. His father was a carpenter. And his father-in-law was a wealthy mill-owner of a nearby town. My mother and grandmother were largely productive of good and substantial meals and children.

“Of Russia, I remember wearing a uniform to school, a book as a gift of scholarship… the smell of lilacs in spring…Father was injured in…the Revolution of 1905…sad farewells upon our leaving for America…I was nine years.”

The autobiography was an assignment for a creative writing class at the University of Pennsylvania taken when he was 31. He was already a successful pharmacist and had supported his six younger brothers and sisters after the cancer-ridden body of his father was placed in the ground when Dad was 15.

Fathering me at 42, his only daughter, became the center of his universe. I learned his ways through osmosis, taking for granted that, should life surprise me, I would simply have to make life work. And, thrust into early widowhood from the same cancerous enemy that had taken my grandfather, I did.

As time passed, I began to understand the importance of writing family stories for those who follow. Legacy leads us to know ourselves and creates strength for our children.

So, a few years ago I began reading and writing memoiristic prose in addition to my academic writing. I found Beth Kephart who, like I, is faculty at Penn.

Beth writes, breathes, tastes feels and celebrates the art of expressing the universal in us all through exquisitely told tales that really happened to the author.

Beth has authored 21 books, including “Handlng the Truth,” a guide to learning to write memoir.

To my delight, Beth and Yale-trained architect husband Bill Sutphin, have just begun Junctures, a series of workshops in beautiful landscape. I signed on for the second workshop. It was in Cape May.

Imagine nine of us, women, all but one. Ages? Say, the mid-forties to mid-seventies. Professions range from psychiatrist to retired English teacher, to real estate expert.

Picture us strewn on fat chairs in the living room of a generous Victorian turned B&B in Cape May. Picture a petite but commanding casually dressed woman, perched on a backless stool, leaning forward, her slim body tensed from riveting attention on her workshop charges.

Twinkle emerging in her eye, she announces topics that lead us to the universal meaning behind carefully selected stories from our lives.

She stresses that memoir draws its power from the intensity of the sensual moments in our lives. Do you remember the smell of your holiday cookie baking? Can you ever forget the first nighttime swim you took in a darkly romantic ocean, teeming with life under your knees? Or swimming with dolphins? Or touching the eyelashes of an elephant?

My hope for 2017 is that my children will not have to scrounge to find the legacy I leave them. My life contains spine-tingling moments, as, no doubt, does yours.

These moments have shaped the future of my offspring and their offspring. They deserve to read about them in years after I cannot tell them stories.

My legacy is to contribute to my children’s’ futures by providing them with a virtual slim black notebook filled with faded pages of simple emotional truths of what it means to be me.

To consider: What is the legacy you need to leave? How do you plan to do this? When?

To Read: Handling the Truth. Beth Kephart. New York, 2013. Penguin-Gotham Books.

Find Judith Coche, Ph.D., helping couples in Stone Harbor and at Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia. Reach her through www.cochecenter.com.

Cape May – Governor Murphy says he doesn't know anything about the drones and doesn't know what they are doing but he does know that they are not dangerous. Does anyone feel better now?