OCEAN VIEW – When Eddie Kobayashi recalls Easter Sunday from his childhood days, one that stands out was in 1942. The then 5-year-old and his family evacuated to an assembly center, a temporary camp used while permanent internment camps were built during World War II.

He recalls the neighbor children, who lived on a farm next door, giving them Easter candy as they left town.

Despite being American citizens, his family, who were of Japanese ancestry, was among nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans held in 10 camps in the nation’s interior after the bombing of Pearl Harbor Dec. 7, 1941.

Sixty-two percent of those in the camps were U.S. citizens.

“The camps were very strict with security,” Kobayashi said, as he compared some of the measures with those of German concentration camps during World War II.

“Double rows of fences so you couldn’t get out, troops, and tanks. My dad didn’t talk about it much after the war, and my mom suffered from depression because she was separated from her family throughout this time. It was a very difficult time.”

Despite harsh beginnings compounded by the Depression, Kobayashi’s parents eventually ended up in Cape May County after the war. As the 81-year-old said, he considers Cape May “his home” and his five siblings “had successful careers.”

His mother and father were florists in Fishing Creek who lived in Cape May. His mother died at 91 in 2004. His father died in 1979.

“I still come down to Cape May,” he said. “I like getting my hair cut there, and seeing friends.”

A 1956 graduate of Cape May High School, the forerunner of Lower Cape May Regional High School, Kobayashi recalled being the third child born to his parents in California during the Depression.

At the time, the family lived on a rented farm, now in the middle of Los Angeles, where they were truck farmers. It was a low-capital business where produce was transported by truck and sold wholesale at farmers markets.

Like many others at the time, families shared what little they had to survive. At one point, his family moved in with his mother’s uncle because that farm could support two families.

All that changed after Pearl Harbor was attacked.

“I was too young to remember the implication of the bombing of Pearl Harbor,” the Philadelphia resident said. “I do remember air raid drills in kindergarten, though, and hiding in large storm drains near the school.”

He recalled that two weeks after the attack, his granduncle and grandfather were picked up by the FBI because they fit the profile of “possible spies or saboteurs.

“My granduncle was a Kendo instructor,” he said referring to a Japanese form of fencing. “He was sent to a federal prison for nine months until he was cleared.

“When my grandfather was picked up, he wasn’t sent to a federal prison because the local sheriff vouched for his character and honesty. He was 70-years-old at the time,” said Kobayashi.

Life changed again for the family when President Roosevelt signed an Executive Order Feb. 19, 1942, giving the Secretary of War and military commanders the authority and power to exclude people from designated areas to defend the nation against sabotage and espionage.

Those edicts included anyone with at least one-sixteenth (equivalent to having one great-great grandparent) of Japanese ancestry. Korean Americans and Taiwanese, classified as ethnically Japanese because both Korea and Taiwan were Japanese colonies at the time, were also included.

No Japanese were allowed in Military Area 1, which included half of the state of California east from the Pacific Ocean, Washington State, Oregon and half of Arizona.

In Military Area 2, people were allowed to roam freely. Eventually, these zones covered about one-third of the U.S. by area.

“We had a week or two to get ready,” the retired electrical engineer said about the Easter Sunday departure for the assembly center. “I remember my parents selling their farm equipment very quickly to get whatever money they could.”

The assembly centers were surrounded by barbed-wire fences, sentry towers with machine guns and searchlights, armed patrol cars and armed guards.

Upon entry, individuals received vaccinations if needed, were interrogated, fingerprinted and assigned a family number.

They were searched for contraband such as weapons, knives longer than six inches, cameras, shortwave radios, and flashlights.

“They disabled the shortwave band in our radio,” Kobayashi said. “Because we were one of the early ones, we got a large stall, 12 feet by 24 feet that was washed, but still smelled like horse manure. We had no furniture. I remember one of my uncles called a family member who was on their way to the center and asked them to bring furniture.”

Kobayashi’s family stayed at the assembly center for seven months before being transported to a camp in Jerome, Ark., by train. He recalled being told by guards to pull down the shades on the train windows when entering a town so the civilians wouldn’t know they were transporting Japanese through their community.

“Jerome wasn’t as tightly secured as far as security measures so the men could go outside the fence and hunt for rattlesnakes, small animals, and little trees to make canes and artwork,” he said.

Coming from southern California, it was the first time the family experienced snow and the heat, humidity, chiggers, and mosquitos that accompany southern summers.

“By the summer of 1943, there was a policy to segregate internees based on their loyalty,” Kobayashi said. “I remember questions 27 and 28 were considered the loyalty oath. If you answered no or refused to answer the question, you were labeled as disloyal.”

Question 27 asked if internees would be “willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?”

Question 28 asked the internees if they would “swear unqualified allegiances to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or other foreign government, power or organization?”

In regard to Question 27, many worried that expressing a willingness to serve would be equated with volunteering for combat, while others felt insulted at being asked to risk their lives for a country that had imprisoned them and their families, according to Wikipedia.

An affirmative answer to Question 28 brought up other issues. Some believed that renouncing their loyalty to Japan would suggest that they had at some point been loyal to Japan and disloyal to the United States.

Many believed they were to be deported to Japan no matter how they answered; they feared an explicit disavowal of the emperor would become known and make such resettlement extremely difficult.

While most camp inmates simply answered “yes” to both questions, several thousand – 17 percent of the total respondents – gave negative or qualified replies out of confusion, fear, or anger at the wording and implications of the questionnaire.

Across the camps, persons who answered “no” to both questions became known as “No Nos.”

Kobayashi’s father was one of many internees who protested the questions as a violation of their constitutional rights and chose not to answer.

“My mom went along with his decision so the family wouldn’t be split up,” he called. “At that point, we were shipped to the concentration camp in Tule Lake, with other disloyal Americans, troublemakers, and internees seeking repatriation.”

Again, the family boarded a train to travel to the isolated area of Tule Lake in northern California, near the Oregon border.

“The summer was hot and dry, and the winter was cold and icy,” he said. “We saw lots of tumbleweeds, found a lot of old shells because the camp was on an old dried out lake bed, and lots of Indian arrow heads. Security was very tight; we could not go outside of the fenced area. There were probably about 1,000 troops there.”

Because the internees didn’t know if they would be returned to Japan or be able to stay in the U.S. after the war ended, Japanese schools sprung up in the camp.

Kobayashi and his siblings attended it and Buddhist services. His father became active in the Organization for Betterment of Camp Conditions (OBCC), comprised of male internees.

“We had such a small amount of food, and no one knew if it was because of the war-time rationing or if someone was stealing it,” Kobayashi said. “It seemed two-thirds of the meat and sugar were missing. So the group decided to have a night watch and the night my dad was on duty, he saw several War Relocation Act (WRA) personnel loading meat onto a truck.

“My dad tried to stop them but was overpowered. Two other internees tried to calm people down, but they were all beaten and accused of being the instigators. My dad was hit over the head with a baseball bat so hard that the bat broke. They all were sent to the stockade.”

This led to a food riot by the internees, and martial law was declared. Military police in tanks, toting machine guns, and tear gas stormed the camp, and 19 members of the OBCC were declared instigators and sent to the stockade for nine months.

An FBI investigation revealed the WRA employees were stealing the food and selling it on the black market.

“The food riots got news coverage and eventually exposed the corruption of the WRA,” Kobayashi said.

His father’s story was told as part of a documentary called “Resistance at Tule Lake,” which is showing across the country this year (http://www.resistanceattulelake.com/about/).

“The movie is quite accurate,” he said. “I attended the showing in Philadelphia and spoke about my experiences afterward. There is a scene in the movie of a man being hit on the head with a bat, but we are not sure if that is my father or not.

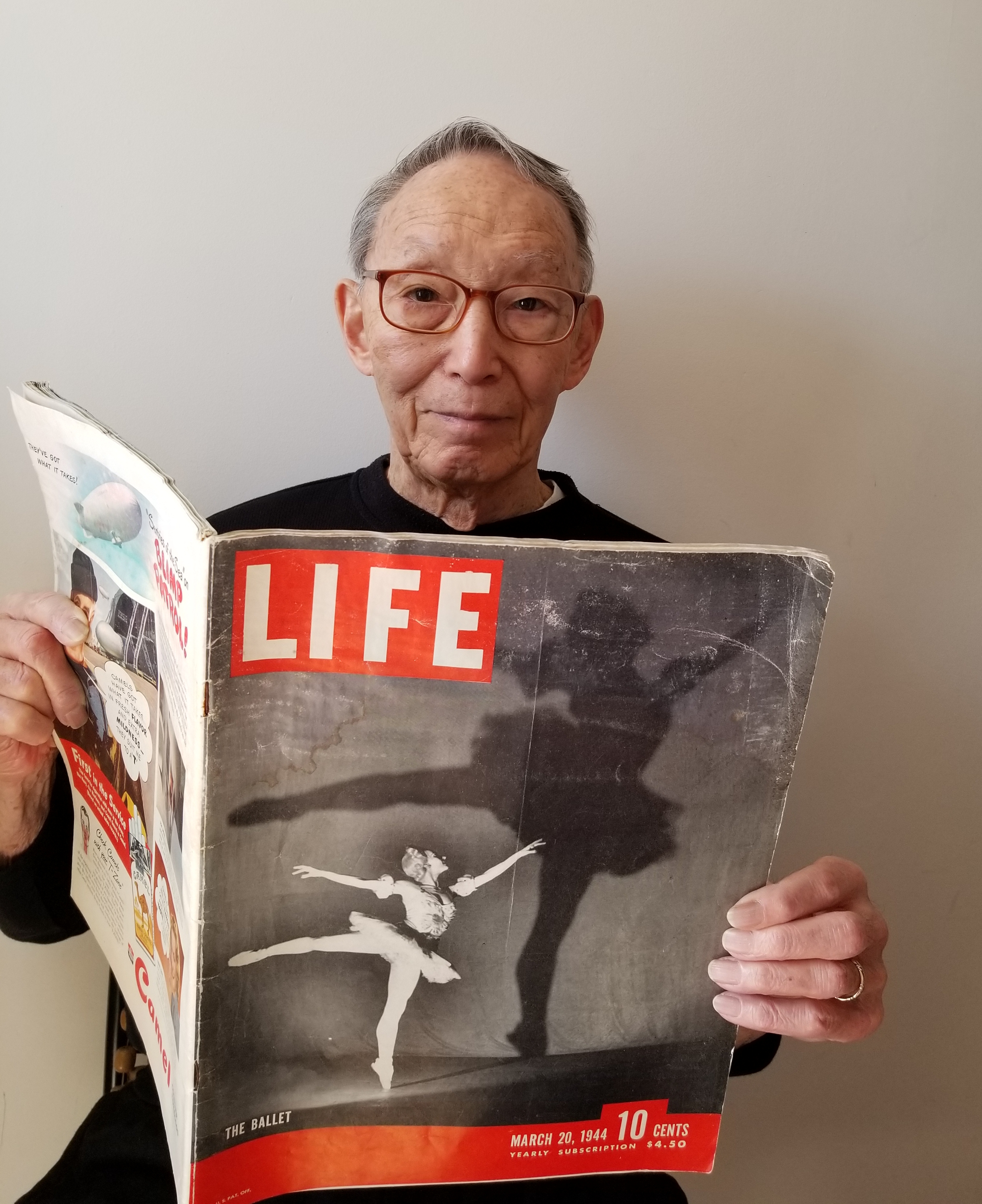

“Life Magazine also did a story about life at Tule Lake in its March 20, 1944, issue,” Kobayashi noted, “and my dad is pictured in one of the photos.”

His story is also on page 210 of the “Personal Justice Denied” report, commissioned by then-President Jimmy Carter to investigate whether internment of civilians was justified.

The story and photo in “Life Magazine” caused strife in the family, however, since some of his uncles and cousins were fighting for the U.S. in World War II. “My father was classified 4F and couldn’t serve,” Kobayashi said. “Others in our family were fighting for the U.S.”

After the war, the WRA suggested Japanese families without land ownership in California relocate to the eastern U.S. Kobayashi’s family ended up in Philadelphia with other Japanese families.

For a short time, the family found work on a farm in Coudersport, Pa. growing potatoes and bush beans. “Life on the farm was very difficult,” he recalled. “We worked there for four and a half years, barely surviving. Then my parents got an opportunity to work on a farm in Ocean View with four other families.

“At Ocean View Farms, we raised lettuce, tomatoes, cantaloupes and cabbages. The crop was abundant, but that drove the price so low we were out of business within two years. While the other families decided to move back to California, my family stayed on as caretakers. My parents worked as florists until they retired.”

Kobayashi’s family has been in the U.S. for more than 100 years. His grandfather immigrated to Hawaii to work on a pineapple plantation in the 1890s. His father was born in 1903 on the Island of Kauai.

(The Kingdom of Hawaii was sovereign from 1810-1893 when the monarchy was overthrown by resident American and European capitalists and landholders. Hawaii was an independent republic from 1894-1898 when it officially became a territory of the U.S. Hawaii was admitted as a U.S. state on Aug. 21, 1959.)

“Anyone who has seen the movie ‘Picture Bride’ knows how difficult life in Hawaii was,” Kobayashi said. “So in 1905, both sets of my grandparents moved to the mainland U.S. through San Francisco.”

The topic of immigration is dear to his heart, as he continues to fight for rights through an organization called the Japanese American Citizens League, established in 1929.

Its mission is to secure civil and human rights of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans and all communities who are affected by injustice and bigotry. It also works to promote and preserve the heritage and legacy of the Japanese-American community.

“We were interned, and we don’t want it to happen again,” Kobayashi said. “You can’t label everyone the same because everyone who is Muslim is not a terrorist, for example. Refugees go through a very thorough vetting process before they are allowed into the U.S. We don’t want what happened to us to happen again.”

To contact Karen Knight, email kknight@cmcherald.com.

Cape May – The number one reason I didn’t vote for Donald Trump was January 6th and I found it incredibly sad that so many Americans turned their back on what happened that day when voting. I respect that the…