CAPE MAY – Cape May adopted the Franklin Street School bond ordinance Nov. 18, and authorized the shared services agreement with the county and the county Library Commission.

The historic school, once a symbol of segregation and exclusion, will become a city branch library and community center. Literally and symbolically, the wall that long separated the city’s children because of race will be breached.

Discussion on this issue began shortly after 6 p.m., and ran for two hours. During the public hearing, 34 individuals spoke. Representatives from the county freeholders, the local school, the county Library Commission, local churches, the county NAACP, and various city committees and boards were in the audience.

Two newly elected state assemblymen spoke. The hostility that had accompanied most council discussions dealing with plans for the Franklin Street side of the city’s municipal block was nowhere to be seen. It was a celebration of Cape May’s commitment to history and preservation.

When the idea was first surfaced, in early 2018, not everyone was supportive of the plan. Almost since Mayor Clarence Lear replaced Edward Mahaney as mayor, the future use of land along Franklin Street, bordered by Lafayette and Washington streets, has been mired in controversy.

An early proposal to designate the entire block as a redevelopment zone generated significant public ire, culminating in a Planning Board meeting, at which it was defeated.

Evolving plans for a new public safety building focused on the area of the school, the existing firehouse and the Firemen’s Museum, leading to concerns about capital costs, loss of parking spaces, proposals to demolish the museum, and the new building’s compatibility with the historic nature of the surrounding area.

Some argued that the space was too small to accommodate the size of the public safety complex the city required.

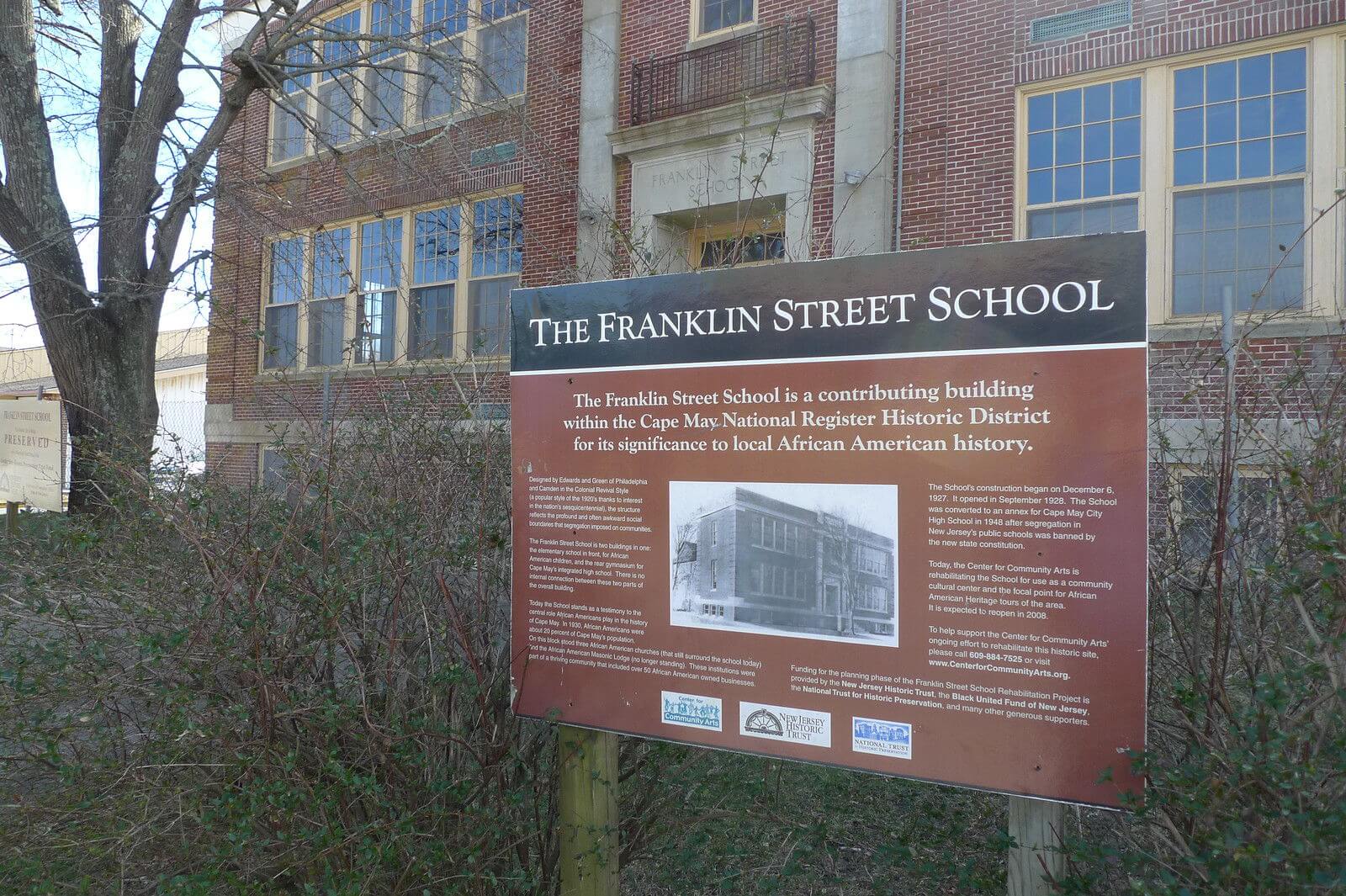

The school building has been deteriorating for years. A local non-profit, the Center for Community Arts, poured $750,000 into structural repairs – money that preserved the building long enough for its new lease on life.

A $6 million project, that saves the historic building and repurposes it as a library and community center, could only be possible with partners willing to participate, and able to fund sizable portions of the effort. The deal on the table, one that speaker after speaker at the public hearing called a “once in a lifetime opportunity,” included a contribution of $2 million from the county and $2 million from the county Library Commission. The goal was in reach if the city could contribute $2 million.

What the council heard repeatedly, across the two hours of discussion on the issue, was the warning that this kind of deal would not come around again easily.

Four votes were needed for an ordinance that had three votes when it was introduced one month before. Zack Mullock, who voted no at the introduction, said that his concerns had been allayed by the formal acceptance of the shared services agreement by the county and the county Library Commission. Lear, Deputy Mayor Patricia Hendricks, and Council member Shaine Meier supported the concept from its inception.

Council member Stacey Sheehan did not support the ordinance. She continued to voice concerns that the building should be preserved, as a community center under city control, leaving the branch library where it is.

During a break in the Nov. 18 proceedings, Deputy City Manager Jerry Inderwies, Jr. said, “It was clear that the votes were there in the first half hour.” He was right, but that did not stop the parade to the podium, where all but one of nearly three dozen speakers celebrated the moment.

Cape May has had its battles over preservation versus development. This was a night for those who wanted to preserve an important part of the city heritage.

The school stands near what was once the heart of a thriving African-American community in the city. One historian of the area, Susan Tischler, estimates that 30% of the city’s population was black in the 1920s. African American labor was an essential ingredient in the success of the early resort.

Much of the history has been lost to demolition, but key elements survive. Across the street from the Franklin Street School is the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, recently damaged in a fire, and the subject of a city-funded study that could lead to a city-sponsored protection for the structure that otherwise might face demolition.

At the corner is the Macedonia Baptist Church, with a historic building next door that is being converted into a Harriet Tubman museum, displaying, among other things, Cape May’s role in the Underground Railroad.

To contact Vince Conti, email vconti@cmcherald.com.

North Wildwood – To the MAGA Seniors of Cape May County who are worried about a potential life at a Nursing Home, this one is for you. The Trump Team and Republicans are preparing to kill a Biden administration…