CAPE MAY – It is likely the former manufactured gas plant here drew water from Cape Island Creek, dumped contaminated water back into that waterway, and established dump locations in the surrounding neighborhood of Lafayette, Broad and St. John streets.

This according to the nation’s foremost expert on former coal-gasification sites, Allen W. Hatheway, a geological engineer with 47 years experience. He has specialized in hazardous waste site characterization and remediation and studied and/or visited more 1,000 sites of former manufactured gas plants.

The gas plant here operated from 1853 to 1937. It produced gas from coal for lighting, heating and cooking and left behind in the ground coal tars, benzene and naphthalene among other toxic chemicals.

The site was inherited by Jersey Central Power and Light (JCP&L) which is responsible for site cleanup.

JCP&L is formulating a remedial action work plan to be submitted to the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) that involves cleaning up what is underground through a water filtration system, rather than digging out the site and hauling away huge quantities of contaminated soil. The utility is in the process of conducting a geophysical study to identify possible underground structures, installing a groundwater pumping well, drilling and collecting soil samples.

Hatheway said the gas works would have required cool, clear water for the “clarification” process to get the tar particles out of the gas. He said it was likely the gas plant drew water from Cape Island Creek and dumped wastewater into the creek called ammoniacal liquor.

Gas plants with access to a waterway had a history of dumping waste into those bodies of water, he said.

It would be typical to have a steam pump to draw water from the creek at the upside of the plant and to discharge “gas liquor” in the creek at the bottom side, said Hatheway. He said there could be some residual contamination in the creek because polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) tend to sequester on silts and clays and on pockets of organic debris.

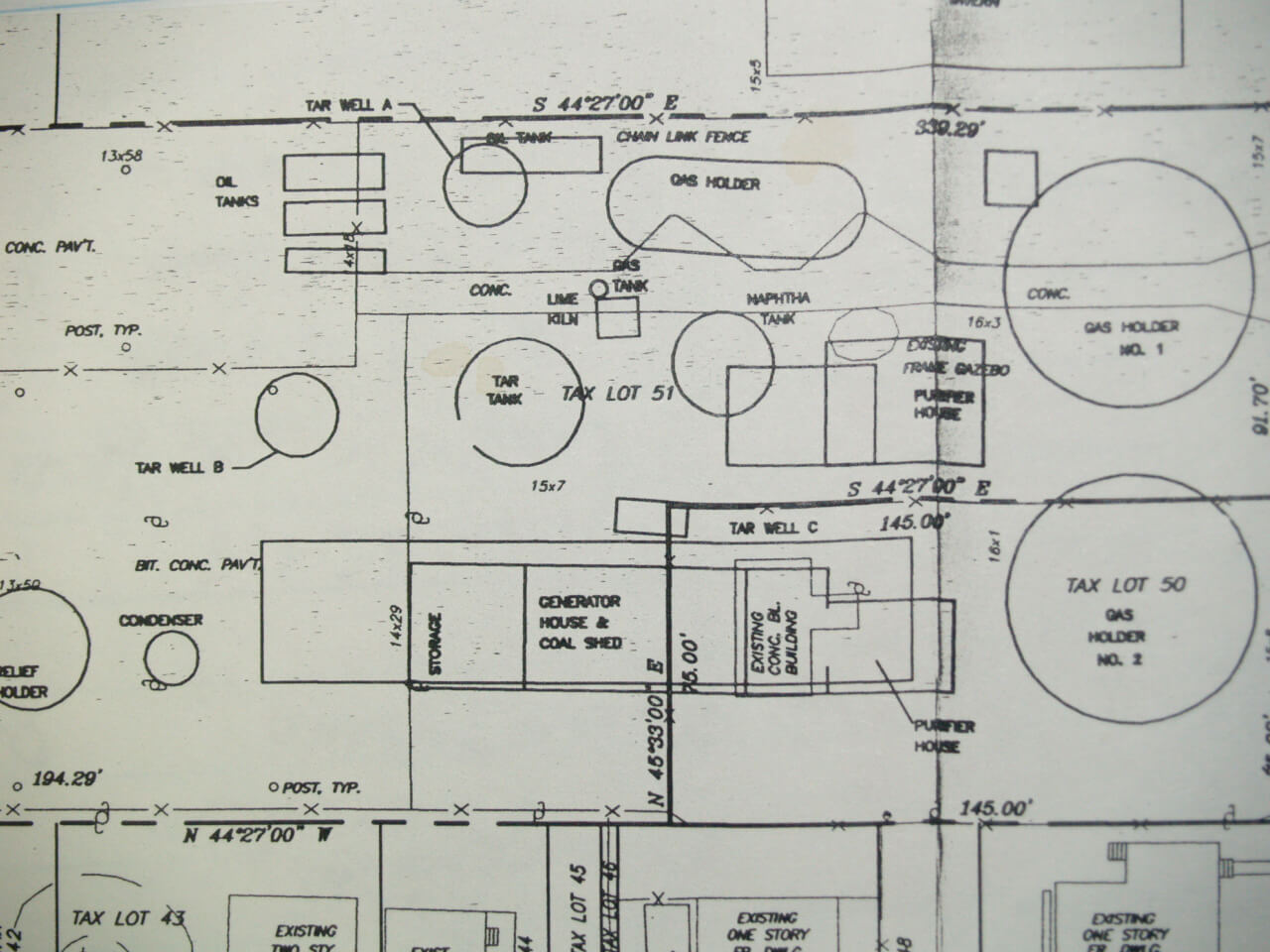

Sanborn maps from 1890, which were made for insurance reasons and showed all structures in the city, available from the City of Cape May, show something 60 feet in length extending from the gas plant to Cape Island Creek. The object is open to interpretation. It may have been a pipe or railroad track.

In addition, a report from consultants McLaren Hart Inc. shows the same structure with a question mark next to it on a chart of the layout of the gas plant.

Historically, dumps for gas works were located along creeks, said Hatheway. Often gas yards had a freely draining surface, so when it rained, contaminants would wash into the creek, he said.

Hatheway said it was likely the plant had a well in the gas yard down to the aquifer.

If so, it would have punched a hole in the protective estuarine clay layer, he said. Old wells at gas plants were never sealed which could become conduits for gas liquors into the aquifer, he continued.

In 2002, Colin Sweeny, former JCP&L director of remediation, said a plume of contaminated groundwater extended into Cape Island Creek and crossed Lafayette Street. He said it was nine feet below ground and flowing from east to west and 14 to 16 lots in the area needed remediation.

From JCP&L’s report on the site, in a zone known as “area of concern two,” a forested, wetland transition area, west of the gas plant towards the creek, contamination was closer to the surface in top soil and fill.

Hatheway said the waste from gas plants was always called “fill.”

“You’ll never see a utility or a consultant call any man-made material on the ground anything other than fill even if it’s loaded with coal tar, bricks, glass, retort debris, cinders, clinker, bits of coke, purifying waste, it’s all fill,” he said.

The gas plant may have dumped waste in any depression or swale in the ground on any vacant land in the vicinity of the gas plant, he said.

Hatheway said an aspect of former gas plant sites that is never discussed is that for every gas works, there was a gas works dump. The dumps were on the gas yard except when they became full.

“Then they moved across the street and into other places in town and created gas works dumps,” said Hatheway.

Hatheway said in his opinion, Cape May’s public housing projects may have been built upon what once served as dumps for the gas plant. He said low-income housing has been built on other gas plant sites around the nation.

Hatheway said gas plants historically dumped waste in a four to five block area from the main operation, sometimes hiring a wagon pulled by mule to cart waste from the gas plant.

Contaminated soil was removed from public housing on Broad Street Court and on the opposite side of Lafayette Street some distance from the known site of the gas plant.

“I suspect what you’ve got is a contaminated gas yard and two dumps,” said Hatheway.

Residuals and waste are present on all gas plant properties which had to be dumped somewhere, he said.

In 2000, seven soil samples were bored from public housing on Broad Street Court. Benzo-anthracene and Benzo-pyrene were detected at a depth of one to five feet below the surface.

In 2002, JCP&L excavated one to six feet of soil on Osborne Court on Cape May Housing Authority property and along Lafayette, Broad and St. John streets. In 2002, tests of soil samples from crawl spaces in public housing on Broad Street found that none exceeded state standards for PAHs.

All told, 10,000 tons of tainted soil have been removed and replaced with clean soil from Wise-Anderson Park, the dog park, Cape May Housing Authority along Broad Street, residential properties along the north side of St. John Street and housing authority property on Lafayette Street.

The question for the Cape May site is where the “box waste, the spent purifier media,” was dumped, said Hatheway. He said cyanide is always present at coal-gas plants and coke ovens.

There would be a lot spent purifying material, he said.

“When it became loaded with the impurities and it could no longer extract any more, they would take it out of the purifier boxes and dump it somewhere,” said Hatheway. “Most of it is sawdust and wood chips and in the coastal communities like yours, the first purifier media was crushed clam shells.”

He said shells were crushed into a crude lime to remove sulfur and cyanide and heavy metal impurities from the coal from the gas. Hatheway said the gas plant site should also have a substance known as “Blue Billy,” a smelly sulfurous, dark gray, clay mass and iron oxide, a brown rusty material.

“The box wastes are always toxic to one degree or another,” said Hatheway. “If the cyanide is there, when it is exposed to air, it turns “Prussian Blue.”

In 2006, when Cape May’s Planning Board turned down an application from a developer to build condominiums on the Vance’s Bar site, which was just north of the plant, then mayor Jerome E. Inderwies remarked there had been health problems in that area for years. Henry Wise Jr., the last owner of the Vance’s Bar, lost his mother, father and aunt to cancer. All had spent a major portion of their lives living or working next to the former gas plant site.

Hatheway said on a national basis, there is circumstantial evidence relating to clusters of cancer around gas yard and gas works dumps.

“It is my feeling there is a lot to be concerned about over long-term, chronic exposure or reception of gas house waste,” said Hatheway.

He said chronic is defined as constant, low level exposure.

While the risk at the Cape May site has been characterized as only a danger if a person ingested contaminated soil or drank contaminated water, Hatheway said there could be a risk of breathing vapors.

There is the possibility that what remains in the ground may volatilize, he said. All PAHs or tars have a volatile characteristic to them and are called volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as light oils, ethyl benzene, toluene, zylene and naphthalene.

He said fumes could come through slabs of buildings, especially a building that has a slab on grade and cracks in the floor. The problem would be worsened in a building without a lot of exchange of air or small rooms. It also accumulates in basements.

The long-term safety of a site is dependent on monitoring which is dependent on the diligence of people, he said. Monitoring wells would be checked by DEP where staff comes and goes over the years.

“What basically happens is 10 years out, the monitoring gets really sloppy and then eventually the reports, unless there is a really tight management system, they just sort of stop,” said Hatheway.

“It’s not a failsafe system for the public,” he said. “Whatever doesn’t get done now, quite frankly, is not in the public interest in the future.”

In a 2003 report from JCP&L on contamination in the “saturated zone,” described as the footprint of the gas plant, running from behind Elsie Wise’s former home on the corner of St. John and Lafayette streets through Wise-Anderson Park to the Vance’s Bar property, naphthalene was detected as high as 6,300 mg/kg, well in excess of an acceptable level of 230 mg/kg. Benzo-anthracene was detected as high as 230 mg/kg well exceeding the state limit of 0.09 mg/kg.

Stone Harbor – Bob Ross thank you for all your years of volunteer service to the community of Stone Harbor. A Lifelong resident And property owner. 10 years on school board, 6 years on zoning board they can't…